On Food and Abolition

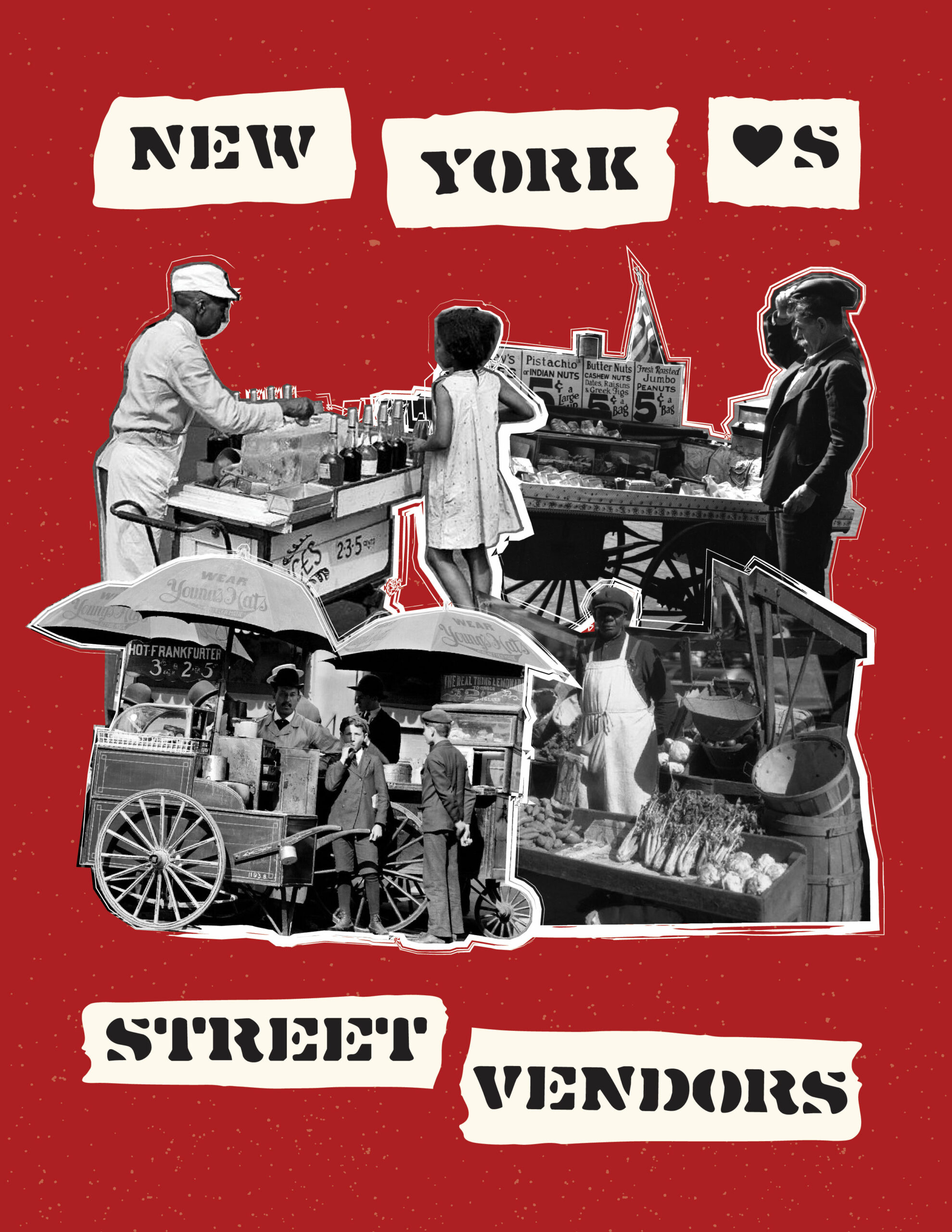

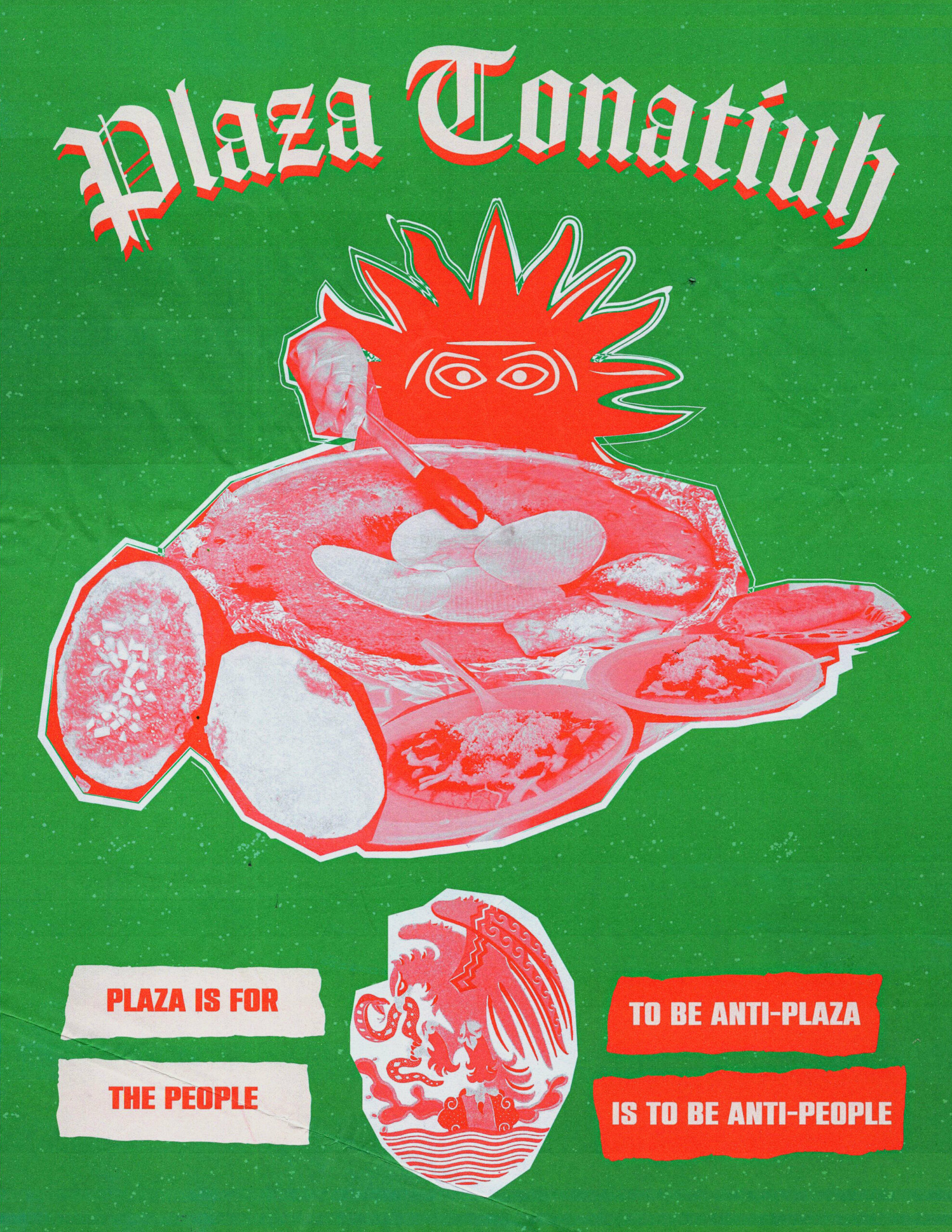

The design of food systems and the carceral state intersect across various axes, from the carceral conditions reproduced by our food systems (like the inhumane conditions for farmworkers, meat processing facilities, and workers across the food supply chain), to the criminalization of poverty in neighborhoods that already lack access to funding for health and nutrition. In this sense, food sovereignty is inextricable from abolition.

Over the past five months our editorial team has worked towards creating this series which considers how the political, social and economic project of prison abolition, ending the prison industrial complex (PIC) and setting in place reparative networks of care, can inform our movement for sovereign food systems. The publishing of the following stories coincides with Black History Month. While it was not our initial intention to publish in February, we draw attention to the ways that the criminal legal system is designed to criminalize, target and fragment Black communities.

In the first two pieces of the series, our contributors ground us in the carceral legacy of agriculture in the United States and the importance of uprooting the legacy with reparative networks of care instead of reproducing structures of violence and racism. On the one year anniversary of the death of 27-year old Weelaunee Forest Defender Manuel “Tortuguita” Teran, professor and author Ashanté M. Reese delves into the history of the proposed site for Atlanta’s Cop City — from plantation, to prison farm, to potential police training grounds. Understanding land’s capacity to hold memory, Ashanté peels back the layers to this carceral palimpsest, and in doing so identifies an alternative, reparative use for the land — one already being seeded by activists and community members who are demonstrating how the site might be a model for food sovereignty.

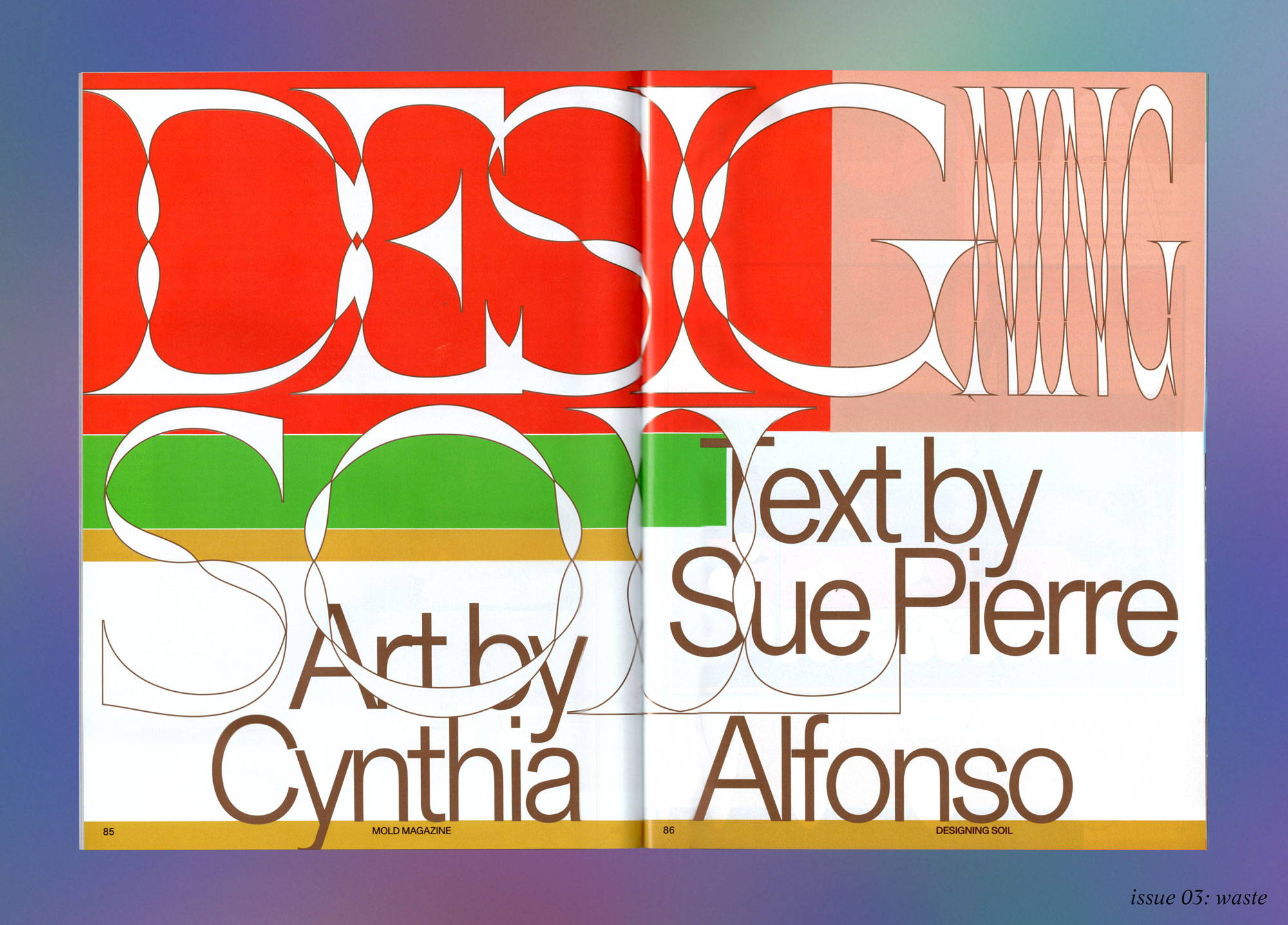

Zooming out, researchers Josh Sbicca and Carrie Chenault outline their work at Prison Agriculture Lab documenting the pervasiveness of prison agriculture through data. Recent reports around inhumane labor conditions and pay within the field have made clear the throughline between America’s history of chattel slavery and the modern prison labor force. Through visualization and storytelling, Josh and Carrie present data as a tool for abolition. In doing so they seek to combat the obfuscation of American food systems’ dependency on the exploitation of incarcerated labor while also empowering abolitionists with a sense of scope and scale of the systems that must be replaced.

This series also asks how food and growing food can be reimagined as a liberatory practice. In an interview with Josh Sbicca, Lawrence Jenkins, who is currently incarcerated in Washington state, shares about his role in building Stafford Creek Corrections Center “green zone,” a prisoner-led agricultural initiative that creates opportunities for inmates to grow their own food and build a food system centered around cooperative as well as solidarity economics. Sara Black of Sweet Freedom Farm reflects on what it means to build an abolitionist farm and situates Sweet Freedom and the burgeoning “Grow Food Not Prisons” movement within Hudson Valley’s broader carceral geographies and trends of displacement.

As Ruth Wilson Gilmore, the scholar and activist, has said, “In order to undo the forces of violence shaping our everyday lives, we would have to change everything.” For many, abolition might seem like an act of subtraction. Honing in on decarceration as an end point, critics might point to the void that is left in its wake. However, an abolitionist framework sees decarceration as a generative step in what is a broader, rigorous commitment to building new systems of care and responsibility for one another. In the final part of our series we speak with people who are doing the work of building abolitionist infrastructures and modeling a path towards a more equitable society. Editor LinYee Yuan speaks with the co-directors of Recess Art, a Brooklyn-based abolitionist art organization, about their Care & Accountability Towards Abolition Framework, and how using this framework as a guideline has transformed how they are creating spaces of resilience for artists and youths in their community. Abolition also requires a radical reimagining of how we eat, something Sweet Freedom Farms founder Jalal Sabur explores with Jon Gray of Ghetto Gastro in their conversation about their work around maple syrup as an abolitionist alternative to sugar and its extractive modes of production.

As a publication constructed around the belief for a just, more resilient future for food and design, abolition and the possibilities it holds as a world-building framework have become central to our ethos. It is abolition that affords us the lens through which to reenvision a more just future at the interlocking matrices of land, labor, and sustenance. In spending time with this series you may discover what we at MOLD hold to be true, that abolition is a durational practice in hope, one that holds the potential of a better future for us all.

With gratitude,

Isabel

Wooden bowl battiyeh, woven basket mikfaya, clay oven tabun, a bed of hot rocks radaf, pillow mold m’khad, a convex metal dome saaj. Sitti Jamila’s crumbling stone barn exists in the architecture of my memories; while her infinitely wrinkled, smiling face surrounded with…